Stringing Together Moby Dick

Hacking with Twine

Games have been around since 3000 BCE (the Royal Game of Ur and Senet are the oldest we have found) and are a continuous source of cooperation, critical thinking, and entertainment. Not only are they a way to bond with others, but they also help us develop analytical skills. Games help us become deeply invested in an idea and create value and meaning using relatively simple tools. Games such as chess and Monopoly are incredibly popular, but video games have rapidly become on of the most popular types of gaming. Video games have an extremely short history, as they started in the 1940’s (look up Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device, if you are curious), but their simulations have captivated millions of people. From Pong to Skyrim, video games are increasingly more immersive and complex, pushing peoples’ imaginations further and further.

Gaming has also become an extremely popular way to teach. Educational games are receiving a lot of recognition as a way to teach children lessons and to keep them interested, but people who are opposed to this type of learning often claim that kids won’t care about anything other than winning. I went to a Hackathon on the Wisconsin campus, where I was able to prototype a game that was meant to teach middle schoolers about the human impact on the environment. The pollution that was created in the game did not stop my greed to have more money than the other players, but the developers were quick to answer how they were in the process of changing that feature. The balance between entertainment and critical thinking is difficult, but not impossible!

An interesting alternative to playing games to help think critically about information is to actually build them! Although most people do not have the skill set to build elaborate games, the Internet has created many open-source platforms to give people the opportunity to be on the creating side of things. By manipulating traditional uses of games, these creators can challenge the notions of what games are, how players interact with them, and how people analyze information.

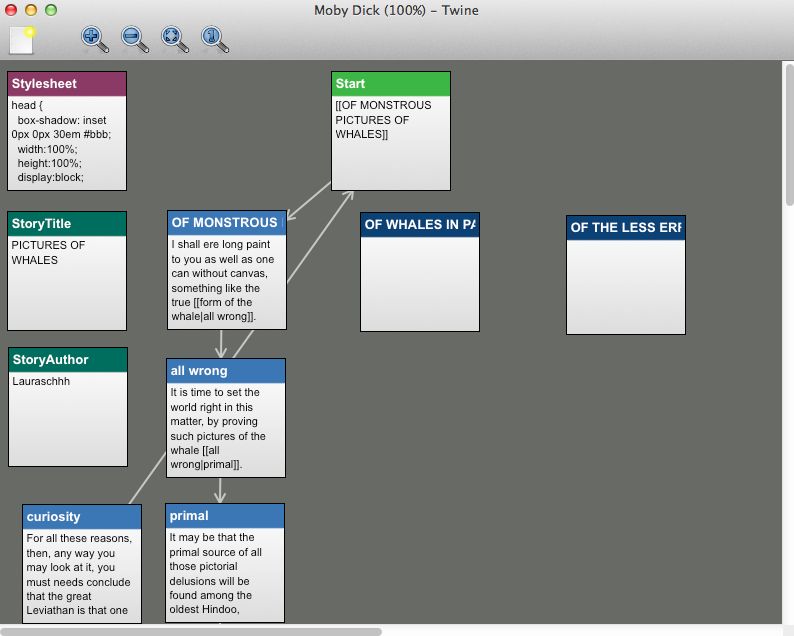

Twine is one of these open-source platforms where anyone can make interactive stories or games. You don’t need to know any code and there is a large community that is ready and willing to help people get started. Twine uses an interactive workstation that let’s you move pages around and connect them with brackets instead of HTML. CSS and Javascript can be used to design the Twine, but it is not necessary, as the default aesthetic is very easy to use. Twine also lets you set variables that create different outcomes depending on how you have interacted with the game. Many stories that are typically created fit into a choose-your-own-adventure storyline and some great examples can be found here and here!

In our Hack Lab, we were instructed to use Twine as a way to interpret a portion of Moby Dick. You can view my Twine here. In it, I took the chapter, “Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales,” and tried to manipulate the structure of the writing. I had a difficult time reading this section, because it is one of the long descriptive chapters, but I was still drawn to why Ishmael took the time to go through the history of whale depictions. As I read the text, I glossed over key points just to make it through the large block paragraphs and I wanted a different affect for my Twine. I broke up the text by separating sentences into paragraphs and paragraphs into completely separate pages. I made the text and images large, so the player can only focus on a few things at the same time. This forces the player to take their time reading the text and to genuinely understand what they were reading.

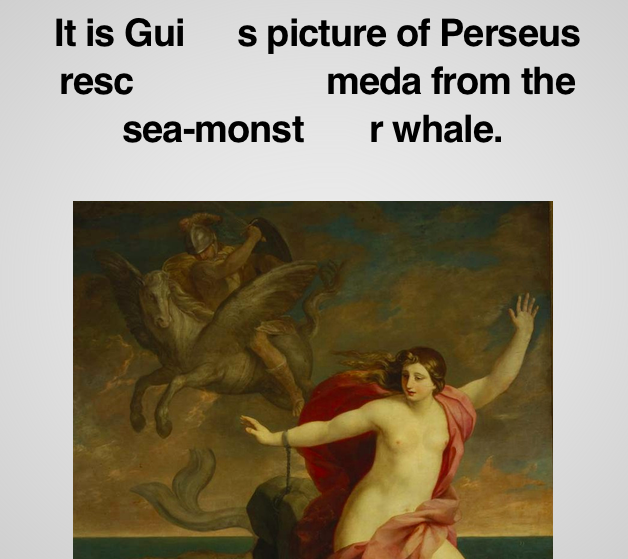

Even as I was creating my Twine, I was able to slow down and really analyze the text. Early on, I was struck by how funny the chapter was. Ishmael’s words are so harsh as he criticizes works of art hundreds of years older than he is and what he says seems so temporary in the grand scheme of things. To highlight this, I made it so the text disappears if the player moves the mouse over the letters, but the pictures stay the way they are. This also causes the player to keep the mouse on the side of the screen, making them focus on the text and not continuously searching for the link that gets them to the next page. The reason the pictures are there at all is to juxtapose Ishmael’s descriptions of the illustrations with the actual images. This way, the player can directly compare what Ishmael is saying to the real images and see if Ishmael’s interpretation of the interpretations is anything close to accurate.

This chapter also helps us think about the Hack Lab as a whole. Ishmael is deeply concerned with translations and interpretations of objects. He believes that these pictures are, “all wrong,” but also goes on to say that there is no way to adequately reach a true description of a whale. Does this mean we should stop trying? Definitely not, Ishmael argues as he spends the rest of the novel trying to interpret whales. By constantly thinking about a text in different ways and figuring out ways to represent it in a new medium (be it through drawing, creating haikus, or making video games), we are able to spend much more time analyzing it. Even as we view these other interpretations (by seeing the picture, reading the poem, or playing the video game), we are able to pick out what others’ deem important and we can think how these perceptions affect the original text. Ishmael might hate it (or fans of a book might hate the movie version), but contributing to the larger discourse in different and unusual ways helps us see the text in a new light and ultimately helps us understand the text better than ever before.